Botanical garden

A botanical garden or botanic garden[nb 1] is a garden with a documented collection of living plants for the purpose of scientific research, conservation, display, and education.[1] It is their mandate as a botanical garden that plants are labelled with their botanical names. It may contain specialist plant collections such as cacti and other succulent plants, herb gardens, plants from particular parts of the world, and so on; there may be glasshouses or shadehouses, again with special collections such as tropical plants, alpine plants, or other exotic plants that are not native to that region.

Most are at least partly open to the public, and may offer guided tours, public programming such as workshops, courses, educational displays, art exhibitions, book rooms, open-air theatrical and musical performances, and other entertainment.

Botanical gardens are often run by universities or other scientific research organizations, and often have associated herbaria and research programmes in plant taxonomy or some other aspect of botanical science. In principle, their role is to maintain documented collections of living plants for the purposes of scientific research, conservation, display, and education, although this will depend on the resources available and the special interests pursued at each particular garden. The staff will normally include botanists as well as gardeners.

Many botanical gardens offer diploma/certificate programs in horticulture, botany and taxonomy. There are many internship opportunities offered to aspiring horticulturists. As well as opportunities for students/researchers to use the collection for their studies.

Definitions

[edit]

The "New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening" (1999) points out that among the various kinds of organizations known as botanical gardens, there are many that are in modern times public gardens with little scientific activity, and it cited a tighter definition published by the World Wildlife Fund and IUCN when launching the "Botanic Gardens Conservation Strategy" in 1989: "A botanic garden is a garden containing scientifically ordered and maintained collections of plants, usually documented and labelled, and open to the public for the purposes of recreation, education and research."[2]

This has been further reduced by Botanic Gardens Conservation International to the following definition which "encompasses the spirit of a true botanic garden":[3] "A botanic garden is an institution holding documented collections of living plants for the purposes of scientific research, conservation, display and education."[4] The following definition was produced by staff of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium of Cornell University in 1976. It covers in some detail the many functions and activities generally associated with botanical gardens:[5]

A botanical garden is a controlled and staffed institution for the maintenance of a living collection of plants under scientific management for purposes of education and research, together with such libraries, herbaria, laboratories, and museums as are essential to its particular undertakings. Each botanical garden naturally develops its own special fields of interests depending on its personnel, location, extent, available funds, and the terms of its charter. It may include greenhouses, test grounds, an herbarium, an arboretum, and other departments. It maintains a scientific as well as a plant-growing staff, and publication is one of its major modes of expression.

This broad outline is then expanded:[5]

The botanic garden may be an independent institution, a governmental operation, or affiliated to a college or university. If a department of an educational institution, it may be related to a teaching program. In any case, it exists for scientific ends and is not to be restricted or diverted by other demands. It is not merely a landscaped or ornamental garden, although it may be artistic, nor is it an experiment station or yet a park with labels on the plants. The essential element is the intention of the enterprise, which is the acquisition and dissemination of botanical knowledge.

Role and functions

[edit]All botanical gardens have their own special interests. In a paper on the role of botanical gardens, Ferdinand von Mueller (1825–1896), the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne (1852–1873), stated, "in all cases the objects [of a botanical garden] must be mainly scientific and predominantly instructive".[6] He detailed many of the objectives being pursued by the world's botanical gardens in the middle of the 19th century, when European gardens were at their height. Many of these are listed below to give a sense of the scope of botanical gardens' activities at that time, and the ways in which they differed from parks or what he called "public pleasure gardens":[6]

- availability of plants for scientific research

- display of plant diversity in form and use

- display of plants of particular regions (including local)

- plants sometimes grown within their particular families

- plants grown for their seed or rarity

- major timber (American English: lumber) trees

- plants of economic significance

- glasshouse plants of different climates

- all plants accurately labelled

- records kept of plants and their performance

- catalogues of holdings published periodically

- research facilities utilising the living collections

- studies in plant taxonomy

- examples of different vegetation types

- student education

- a herbarium

- selection and introduction of ornamental and other plants to commerce

- studies of plant chemistry (phytochemistry)

- report on the effects of plants on livestock

- at least one collector maintained doing field work

Botanical gardens have always responded to the interests and values of the day. If a single function were to be chosen from the early literature on botanical gardens, it would be their scientific endeavour and, flowing from this, their instructional value. In their formative years, botanical gardens were gardens for physicians and botanists, but they became more associated with ornamental horticulture and the needs of the general public. The scientific reputation of a botanical garden is judged by the publications coming out of herbaria and similar facilities, not by its living collections.[7] Their focus has been on creating an awareness of the threat to the Earth's ecosystems from human populations and its consequent need for biological and physical resources. Botanical gardens provide an excellent medium for communication between the world of botanical science and the general public. Education programs can help the public develop greater environmental awareness by understanding the meaning and importance of ideas like conservation and sustainability.[8]

Worldwide network

[edit]

Worldwide, there are now about 1800 botanical gardens and arboreta in about 150 countries (mostly in temperate regions) of which about 550 are in Europe (150 of which are in Russia),[9] 200 in North America,[10] and an increasing number in East Asia.[11] These gardens attract about 300 million visitors a year.[12]

Historically, botanical gardens exchanged plants through the publication of seed lists (called Latin: Indices Seminae in the 18th century). This was a means of transferring both plants and information between botanical gardens. This system continues today, though with attention to the risks of genetic piracy and transmission of invasive species.[13]

The International Association of Botanic Gardens[14] was formed in 1954 as a worldwide organisation affiliated to the International Union of Biological Sciences. More recently, coordination has also been provided by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), which has the mission "To mobilise botanic gardens and engage partners in securing plant diversity for the well-being of people and the planet".[15]

Regional co-ordination is seen in the United States with the American Public Gardens Association[16] (formerly the American Association of Botanic Gardens and Arboreta), while in Australasia there is the Botanic Gardens of Australia and New Zealand (BGANZ).[17]

History

[edit]The history of botanical gardens is closely linked to the history of botany itself. The botanical gardens of the 16th and 17th centuries were medicinal gardens, but the idea of a botanical garden changed to encompass displays of the beautiful, strange, new and sometimes economically important plant trophies being returned from the European colonies and other distant lands.[18] In the 18th century, they became more educational in function, demonstrating the latest plant classification systems devised by botanists working in the associated herbaria as they tried to order these new treasures. Then, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the trend was towards a combination of specialist and eclectic collections demonstrating aspects of both horticulture and botany.[19]

Precursors

[edit]The idea of "scientific" gardens used specifically for the study of plants dates back to antiquity.[20] The origin of modern botanical gardens is generally traced to the appointment of botany professors to the medical faculties of universities in 16th-century Renaissance Italy, which entailed curating a medicinal garden. However, the objectives, content, and audience of today's botanic gardens more closely resembles that of the grandiose gardens of antiquity and the educational garden of Theophrastus in the Lyceum of ancient Athens.[21]

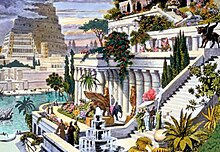

Grand gardens of ancient history

[edit]

Near-eastern royal gardens set aside for economic use or display and containing at least some plants gained by special collecting trips or military campaigns abroad, are known from the second millennium BCE in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Crete, Mexico and China.[23] In about 2800 BCE, the Chinese Emperor Shen Nung sent collectors to distant regions searching for plants with economic or medicinal value.[24] It has also been suggested that the Spanish colonization of Mesoamerica influenced the history of the botanical garden[20] as gardens in Tenochtitlan established by king Nezahualcoyotl,[25] also gardens in Chalco (altépetl) and elsewhere, greatly impressed the Spanish invaders, not only with their appearance, but also because the indigenous Aztecs employed many more medicinal plants than did the classical world of Europe.[26][27]

Early medieval gardens in Islamic Spain resembled later botanic gardens, an example being the 11th-century Huerta del Rey garden of physician and author Ibn Wafid (999–1075 CE) in Toledo. This was taken over by garden chronicler Ibn Bassal (fl. 1085 CE) until the Christian conquest in 1085 CE. Ibn Bassal then founded a garden in Seville, most of its plants being collected on a botanical expedition that included Morocco, Persia, Sicily, and Egypt. The medical school of Montpellier was also founded by Spanish Arab physicians, and by 1250 CE, it included a physic garden, but the site was not given botanic garden status until 1593.[28]

Physic gardens

[edit]Botanical gardens developed from physic gardens, whose main purpose was to cultivate herbs for medical use as well as research and experimentation. Such gardens have a long history. In Europe, for example, Aristotle (384 BCE – 322 BCE) is said to have had a physic garden in the Lyceum at Athens, which was used for educational purposes and for the study of botany, and this was inherited, or possibly set up, by his pupil Theophrastus, the "Father of Botany".[29][30] There is some debate among science historians whether this garden was ordered and scientific enough to be considered "botanical"; instead, they attribute the earliest known botanical garden in Europe to the botanist and pharmacologist Antonius Castor, mentioned by Pliny the Elder in the 1st century.[31]

The forerunners of modern botanical gardens are generally regarded as being the medieval monastic physic gardens that originated after the decline of the Roman Empire at the time of Emperor Charlemagne (742–789 CE). These contained a hortus, a garden used mostly for vegetables, and another section set aside for specially labelled medicinal plants and this was called the herbularis or hortus medicus—more generally known as a physic garden, and a viridarium or orchard.[32] Such gardens were given impetus by Charlemagne's Capitulary de Villis, which listed 73 herbs to be used in the physic gardens of his dominions. Many of these had already been introduced to British gardens.[33] Pope Nicholas V set aside part of the Vatican grounds in 1447, for a garden of medicinal plants that were used to promote the teaching of botany, and this was a forerunner to the University gardens at Padua and Pisa established in the 1540s.[34] Certainly the founding of many early botanic gardens was instigated by members of the medical profession.[35]

16th- and 17th-century European gardens

[edit]

In the 17th century, botanical gardens began their contribution to a deeper scientific curiosity about plants. If a botanical garden is defined by its scientific or academic connection, then the first true botanical gardens were established with the revival of learning that occurred in the European Renaissance. These were secular gardens attached to universities and medical schools, used as resources for teaching and research. The superintendents of these gardens were often professors of botany with international reputations, a factor that probably contributed to the creation of botany as an independent discipline rather than a descriptive adjunct to medicine.[36]

Origins in the Italian Renaissance

[edit]The botanical gardens of Southern Europe were associated with university faculties of medicine and were founded in Italy at Orto botanico di Pisa (1544), Orto botanico di Padova (1545), Orto Botanico di Firenze (1545), Orto Botanico dell'Università di Pavia (1558) and Orto Botanico dell'Università di Bologna (1568).[nb 2] Here the physicians (known in English as apothecaries) delivered lectures on the Mediterranean "simples" or "officinals" that were being cultivated in the grounds. Student education was no doubt stimulated by the relatively recent advent of printing and the publication of the first herbals.[37]

Northern Europe

[edit]The tradition of these Italian gardens spread across Europe, including among the earliest gardens Leipzig Botanical Garden, Germany, 1543,[38] the Botanical Garden of Valencia, Spain, 1567;[39] Hortus Botanicus Leiden, Netherlands, 1590;[40] and Hortus Botanicus (Amsterdam), Netherlands, 1638),[41] University of Oxford Botanic Garden, England, 1621;[42] and Chelsea Physic Garden, England, 1673;[43] Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Scotland, 1670;[44] Jardin des plantes de Montpellier, France, 1593;[45] and Jardin des Plantes, Paris, 1635;[46] University of Copenhagen Botanical Garden, Denmark, 1600;[47] and Uppsala University, Sweden, 1655.[48]

Beginnings of botanical science

[edit]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the first plants were being imported to these major Western European gardens from Eastern Europe and nearby Asia (which provided many bulbs), and these found a place in the new gardens, where they could be conveniently studied by the plant experts of the day. For example, Asian introductions were described by Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), who was director, in turn, of the Botanical Garden of the University of Vienna and Hortus Botanicus Leiden. Many plants were being collected from the Near East, especially bulbous plants from Turkey. Clusius laid the foundations of Dutch tulip breeding and the bulb industry, and he helped create one of the earliest formal botanical gardens of Europe at Leyden where his detailed planting lists have made it possible to recreate this garden near its original site. The hortus medicus of Leyden in 1601 was a perfect square divided into quarters for the four continents, but by 1720, though, it was a rambling system of beds, struggling to contain the novelties rushing in,[49] and it became better known as the hortus academicus. His Exoticorum libri decem (1605) is an important survey of exotic plants and animals that is still consulted today.[50]

In the mid to late 17th century, the Paris Jardin des Plantes was a centre of interest with the greatest number of new introductions to attract the public. In England, the Chelsea Physic Garden was founded in 1673 as the "Garden of the Society of Apothecaries". The Chelsea garden had heated greenhouses, and in 1723 appointed Philip Miller (1691–1771) as head gardener. He had a wide influence on both botany and horticulture, as plants poured into it from around the world. The garden's golden age came in the 18th century, when it became the world's most richly stocked botanical garden. Its seed-exchange programme was established in 1682 and still continues today.[51]

18th century

[edit]Gardens and orangeries

[edit]

With the increase in maritime trade, ever more plants were brought back to Europe as trophies from distant lands, and these were triumphantly displayed in the private estates of the wealthy, in commercial nurseries, and in the public botanical gardens. Heated conservatories called "orangeries" became a feature of many botanical gardens.[52]

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew were founded in 1759, initially as part of the Royal Garden set aside as a physic garden. William Aiton (1741–1793), the first curator, was taught by garden chronicler Philip Miller of the Chelsea Physic Garden whose son Charles became first curator of the original Cambridge Botanic Garden (1762).[53] In 1759, the "Physick Garden" was planted, and by 1767, it was claimed that "the Exotick Garden is by far the richest in Europe".[54] Gardens such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (1759) and Orotava Acclimatization Garden (in Spanish), Tenerife (1788) and the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid (1755) were set up to cultivate new species returned from expeditions to the tropics; they also helped found new tropical botanical gardens. From the 1770s, following the example of the French and Spanish, amateur collectors were supplemented by official horticultural and botanical plant hunters.[55] These botanical gardens were boosted by the flora being sent back to Europe from various European colonies around the globe.[56]

At this time, British horticulturalists were importing many woody plants from Britain's colonies in North America, and the popularity of horticulture had increased enormously, encouraged by the horticultural and botanical collecting expeditions overseas fostered by the directorship of Sir William Jackson Hooker and his keen interest in economic botany.[57] At the end of the 18th century, Kew, under the directorship of Sir Joseph Banks, enjoyed a golden age of plant hunting, sending out collectors to the South African Cape, Australia, Chile, China, Ceylon, Brazil, and elsewhere,[58] and acting as "the great botanical exchange house of the British Empire".[59] From its earliest days to the present, Kew has in many ways exemplified botanic garden ideals, and is respected worldwide for the published work of its scientists, the education of horticultural students, its public programmes, and the scientific underpinning of its horticulture.[60]

In 1728, John Bartram founded Bartram's Garden in Philadelphia, one of the continent's first botanical gardens. The garden is now managed as a historical site that includes a few original and many modern specimens as well as extensive archives and restored historical farm buildings.[61][62]

Plant classification

[edit]The large number of plants needing description were listed in garden catalogues; and from 1753 Carl Linnaeus established the system of binomial nomenclature which greatly facilitated the listing process. Names of plants were authenticated by dried plant specimens mounted on card (a hortus siccus or garden of dried plants) that were stored in buildings called herbaria, these taxonomic research institutions being frequently associated with the botanical gardens, many of which by then had "order beds" to display the classification systems being developed by botanists in the gardens' museums and herbaria. Botanical gardens became scientific collections, as botanists published their descriptions of the new exotic plants, and these were recorded for posterity in detail by superb botanical illustrations. Botanical gardens effectively dropped their medicinal function in favour of scientific and aesthetic priorities, and the term "botanic garden" came to be more closely associated with the herbarium, library (and later laboratories) housed there than with the living collections – on which little research was undertaken.[63]

19th century

[edit]

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were marked by the establishment of tropical botanical gardens as a tool of colonial expansion (for trade and commerce and, secondarily, science) mainly by the British and Dutch, in India, South-east Asia and the Caribbean.[64] This was also the time of Sir Joseph Banks's botanical collections during Captain James Cook's circumnavigations of the planet and his explorations of Oceania, with plant introductions on a grand scale.[65]

Tropical

[edit]There are currently about 230 tropical botanical gardens, many of them in southern and south-eastern Asia.[66] The first botanical garden founded in the tropics was the Pamplemousses Botanical Garden in Mauritius, established in 1735 to provide food for ships using the port, but later trialling and distributing many plants of economic importance. This was followed by the West Indies (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Botanic Gardens, 1764) and in 1786 by the Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Botanical Garden in Calcutta, India founded during a period of prosperity when the city was a trading centre for the Dutch East India Company.[67] Other gardens were constructed in Brazil (Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden, 1808), Sri Lanka (Botanic Gardens of Peradeniya, 1821 and on a site dating back to 1371), Indonesia (Bogor Botanical Gardens, 1817 and Kebun Raya Cibodas, 1852), and Singapore (Singapore Botanical Gardens, 1822). These had a profound effect on the economy of the countries, especially in relation to the foods and medicines introduced. The importation of rubber trees to the Singapore Botanic Garden initiated the important rubber industry of the Malay Peninsula. At this time also, teak and tea were introduced to India and breadfruit, pepper and starfruit to the Caribbean.[10]

Included in the charter of these gardens was the investigation of the local flora for its economic potential to both the colonists and the local people. Many crop plants were introduced by or through these gardens – often in association with European botanical gardens such as Kew or Amsterdam – and included cloves, tea, coffee, breadfruit, cinchona, sugar, cotton, palm oil and Theobroma cacao (for chocolate).[64] During these times, the rubber plant was introduced to Singapore.[68] Especially in the tropics, the larger gardens were frequently associated with a herbarium and museum of economy.[69] The Botanical Garden of Peradeniya had considerable influence on the development of agriculture in Ceylon where the Para rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) was introduced from Kew, which had itself imported the plant from South America.[64] Other examples include cotton from the Chelsea Physic Garden to the Province of Georgia in 1732 and tea into India by Calcutta Botanic Garden.[70] The transfer of germplasm between the temperate and tropical botanical gardens was undoubtedly responsible for the range of agricultural crops currently used in several regions of the tropics.[71]

Temperate

[edit]The first botanical gardens in Australia were founded early in the 19th century. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 1816; the Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens, 1818; the Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne, 1845; Adelaide Botanic Gardens, 1854; and Brisbane Botanic Gardens, 1855. These were established essentially as colonial gardens of economic botany and acclimatisation.[72]

South Africa has ten national level botanical gardens, all overseen by the South African National Biodiversity Institute.[73] The oldest botanical garden in South Africa is the Durban Botanic Gardens which has been on the same site since 1851. The Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden is the most famous and developed garden in the country, established in 1913 on a site dating to 1848 and covering 36 hectares, with an additional 528 hectares of mountainside wilderness that forms part of the garden.[74] Stellenbosch University Botanical Garden is South Africa's oldest university botanical garden;[75] it was established in 1922. Also in the country is the Karoo Desert National Botanical Garden, founded in 1921 and relocated in 1945.[76] The Orman Garden at Giza in Egypt was founded in 1875.[77]

Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, all experienced farmers, shared the dream of a national botanic garden, leading to the founding in 1820 of the United States Botanic Garden,[78] next to the Capitol in Washington DC. In 1859, the Missouri Botanical Garden was founded at St Louis, Missouri; it is one of the world's leading gardens specializing in tropical plants.[62]

Russia's botanical gardens include Moscow University Botanic Garden ('the Apothecary Garden'), (1706) founded by Tsar Peter the Great,[79] and the Saint Petersburg Botanical Garden, (1714).[80]

20th century

[edit]

Civic and municipal botanical gardens

[edit]A large number of civic or municipal botanical gardens were founded in the 19th and 20th centuries. These did not develop scientific facilities or programmes, but the horticultural aspects were strong and the plants often labelled. They were botanical gardens in the sense of building up collections of plants and exchanging seeds with other gardens around the world, although their collection policies were determined by those in day-to-day charge of them. They tended to become little more than beautifully maintained parks and were, indeed, often under general parks administrations.[81]

Community engagement

[edit]The second half of the 20th century saw increasingly sophisticated educational, visitor service, and interpretation services. Botanical gardens started to cater for many interests and their displays reflected this, often including botanical exhibits on themes of evolution, ecology or taxonomy, horticultural displays of attractive flowerbeds and herbaceous borders, plants from different parts of the world, special collections of plant groups such as bamboos or roses, and specialist glasshouse collections such as tropical plants, alpine plants, cacti and orchids, as well as the traditional herb gardens and medicinal plants. Specialised gardens like the Palmengarten in Frankfurt, Germany (1869), one of the world's leading orchid and succulent plant collections, have been very popular.[13] With decreasing financial support from governments, revenue-raising public entertainment increased, including music, art exhibitions, special botanical exhibitions, theatre and film, this being supplemented by the advent of "Friends" organisations and the use of volunteer guides.[82]

Plant conservation

[edit]Plant conservation and the heritage value of exceptional historic landscapes were treated with a growing sense of urgency through the 20th century. Specialist gardens were sometimes given a separate or adjoining site, to display native and indigenous plants.[2] In the 1970s, gardens became focused on plant conservation. The Botanic Gardens Conservation Secretariat was established by the IUCN, and the World Conservation Union in 1987 with the aim of coordinating the plant conservation efforts of botanical gardens around the world. It maintains a database of rare and endangered species in botanical gardens' living collections. Many gardens hold ex situ conservation collections that preserve genetic variation. These may be held as seeds dried and stored at low temperature, or in tissue culture (such as the Kew Millennium Seedbank); as living plants, including those that are of special horticultural, historical or scientific interest (such as those in the National Plant Collection in the United Kingdom); or by managing and preserving areas of natural vegetation. Collections are often held and cultivated with the intention of reintroduction to their original habitats.[83]

21st century

[edit]New gardens

[edit]

Botanical gardens have continued to be built in the 21st century, such as the first botanical garden in Oman, which is planned to be one of the largest gardens in the world, with the first large-scale cloud forest in a huge glasshouse.[10][84] Development of botanical gardens in China over recent years has been remarkable, including the Hainan Botanical Garden of Tropical Economic Plants at Guangzhou,[85] South China Botanical Garden the Xishuangbanna Botanical Garden of Tropical Plants and the Xiamen Botanic Garden,[86] but in developed countries, many have closed for lack of financial support, this being especially true of botanical gardens attached to universities.[2] The Palestine Museum of Natural History has a botanic garden, which has been described as a site of nation-building and resistance by Silvia Hassouna.[87]

Missions and strategy

[edit]The Center for Plant Conservation at St Louis, Missouri, coordinates the conservation of native North American species.[88] The 2006 North American Botanic Garden Strategy for Plant Conservation sets out its goals to document and conserve plant diversity, to use that diversity sustainably, to educate the public about plant diversity, build conservation capacity, and to build support for the strategy itself.[89]

A 2024 review in a special issue of the Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens on the sustainability of botanic gardens noted their increasing roles in conservation and research, and the many new gardens created since 1950. In its view, the gardens are being "reinvent[ed]" to serve the goals of conservation, sustainability, and social engagement. It observes that historically, the gardens emerged in an era that saw both the growth of modern science and the colonial era. In response, the gardens have engaged in decolonising and in "new socio-environmental missions". Finally, it attempts to view the gardens on a global scale.[90] A 2023 historical review by Chinese botanists similarly notes the long history of botanical gardens from the medicinal gardens of the first universities in Renaissance Europe, and from China's ancient Shennong herbal garden tradition. The gardens have in its view continuously adapted to new demands in a changing environment, coming to serve the "core mission of ex situ conservation".[91]

Botanical gardens must find a compromise between the need for peace and seclusion, while at the same time satisfying the public need for information and visitor services that include restaurants, information centres and sales areas that bring with them rubbish, noise, and hyperactivity. Attractive landscaping and planting design sometimes compete with scientific interests — with science now often taking second place. Some gardens are now heritage landscapes that are subject to constant demand for new exhibits and exemplary environmental management.[92]

See also

[edit]- Herb farm

- List of botanical gardens

- Plant collecting

- National Public Gardens Day

- Botanical and horticultural library

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The terms botanic and botanical and garden or gardens are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word botanic is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens.

- ^ Precisely dating the foundation of botanical gardens is often difficult because government decrees may be issued some time before land is acquired and planting begins, or existing gardens may be relocated to new sites, or previously existing gardens may be taken over and converted.

References

[edit]- ^ EPIC. "Botanic Gardens and Plant Conservation". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Huxley 1992, p. 375

- ^ Wyse Jackson & Sutherland 2000, p. 12

- ^ Wyse Jackson 1999, p. 27

- ^ a b Bailey & Bailey 1978, p. 173

- ^ a b Mueller 1871

- ^ Heywood 1987, p. 16

- ^ Drayton 2000, pp. 269–274

- ^ Gratani, Loretta (15 January 2008). "Growth pattern and photosynthetic activity of different bamboo species growing in the Botanical Garden of Rome". Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants. 203 (1): 77–84. Bibcode:2008FMDFE.203...77G. doi:10.1016/j.flora.2007.11.002 – via Science Direct.

- ^ a b c "The History of Botanic Gardens". BGCI.org. BGCI. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "东亚植物园". East Asia Botanic Gardens Network. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Williams, Sophie J.; Jones, Julia P. G.; Gibbons, James M.; Clubbe, Colin (20 February 2015). "Botanic gardens can positively influence visitors' environmental attitudes" (PDF). Biodiversity and Conservation. 24 (7): 1609–1620. Bibcode:2015BiCon..24.1609W. doi:10.1007/s10531-015-0879-7. S2CID 15572584.

- ^ a b Heywood 1987, p. 11

- ^ "International Association of Botanic Gardens (IABG)". BGCI.org. Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Mission statement". BGCI.org. Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "American Public Gardens Association". publicgardens.org. American Public Gardens Association. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Welcome to BGANZ". BGANZ.org.au. Botanic Gardens Australia and New Zealand Inc. 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 210

- ^ Hill 1915, pp. 219–223

- ^ a b Hyams & MacQuitty 1969, p. 12

- ^ Spencer & Cross 2017, p. 56

- ^ Dalley 1993, p. 113

- ^ Day 2010, pp. 65–78

- ^ Hill 1915, pp. 185–186

- ^ Toby Evans 2010, pp. 207–219

- ^ Guerra 1966, pp. 332–333

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 187

- ^ Taylor 2006, p. 57

- ^ Young 1987, p. 7

- ^ Thanos 2005

- ^ Sarton, George (1952). Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece. Dover classics of science and mathematics. Dover Publications. p. 556. ISBN 9780486274959.

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 188

- ^ Holmes 1906, pp. 49–50

- ^ Hyams & MacQuitty 1969, p. 16

- ^ Holmes 1906, p. 54

- ^ Williams 2011, p. 148

- ^ Hill 1915, pp. 190–197

- ^ "Botanischer Garten der Universität Leipzig". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Jardí Botànic de la Universitat de València". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Hortus Botanicus Leiden". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Oxford Botanic Garden & Arboretum". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Chelsea Physic Garden". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Jardins des Plantes, Université Montpellier". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Jardins des Plantes, Paris (MNHN)". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Natural History Museum of Denmark Botanical Garden". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "The Linnaean Gardens of Uppsala". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ Drayton 2000, p. 24

- ^ See Ogilvie 2006

- ^ See Minter 2000

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 200

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 205

- ^ Bute in Drayton 2000, p. 43

- ^ Drayton 2000, p. 46

- ^ Drayton 2000, p. xi

- ^ Drayton 2000, pp. 93–94

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 207

- ^ Drayton 2000, p. xiii

- ^ See Desmond 2007

- ^ "HALS No. PA-1, John Bartram House & Garden" (PDF). Historic American Landscapes Survey. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b Huxley 1992, p. 376

- ^ Heywood 1987, p. 7

- ^ a b c Heywood 1987, p. 9

- ^ Gooley, Tristan (2012). The Natural Explorer. London: Sceptre. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-444-72031-0.

- ^ Heywood 1987, p. 13

- ^ Heywood 1987, p. 8

- ^ Hill 1915, pp. 212–213

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 213

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 222

- ^ Heywood 1987, p. 10

- ^ Looker in Aitken & Looker 2002, p. 98

- ^ "National botanical gardens include Kirstenbosch, Harold Porter, Walter Sisulu, Pretoria, Lowveld, Free State and KwaZulu-Natal; local botanical gardens include Johannesburg and Durban". www.southafrica.net. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Kirstenbosch National Botanical Gardens, Cape Town". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Stellenbosch University Botanical Garden". Stellenbosch University. Retrieved 2 February 2025.

- ^ "Karoo Desert: History". South African National Biodiversity Institute. Retrieved 2 February 2025.

- ^ "Orman Botanic Garden". Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Brief History of the U.S. Botanic Garden". usbg.gov. United States Botanic Garden. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Aptekarsky Ogorod". Gardenvisit.com. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ Desmond, Ray (1994). Dictionary Of British And Irish Botanists And Horticulturists Including plant collectors, flower painters and garden designers. CRC Press. p. 284.

- ^ Heywood 1987, pp. 10–16

- ^ Looker in Aitken & Looker 2002, pp. 99–100

- ^ See Simmons et al. 1976

- ^ "The Project : Muscat, Oman". Oman Botanic Garden. 2025. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Hainan Botanical Garden of Tropical Economic Plants". BGCI.org. Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Heywood 1987, p. 12

- ^ Hassouna, Silvia (13 September 2023). "Cultivating biodiverse futures at the (postcolonial) botanical garden". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 49 (2). doi:10.1111/tran.12639.

- ^ Huxley 1992, p. 377

- ^ "North American Botanic Garden Strategy for Plant Conservation" (PDF). Botanic Gardens Conservation International. 2006.

- ^ Neves, Katja Grötzner (31 May 2024). "Botanic Gardens in Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainability: History, Contemporary Engagements, Decolonization Challenges, and Renewed Potential". Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens. 5 (2): 260–275. doi:10.3390/jzbg5020018.

- ^ Liao, Jingping; Ni, Dujuan; He, Tuo; Huang, Hongwen (2023). "Historical review, current status and future prospects of global botanical gardens". Biodiversity Science. 31 (9): 23256. doi:10.17520/biods.2023256. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Environmental management". Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne. 8 June 2010. Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aitken, Richard & Looker, Michael, eds. (2002). The Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-553644-7.

- Bailey, Liberty Hyde & Bailey, Ethel Z. (1978). Hortus Third. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-505470-7.

- Dalley, Stephanie (1993). "Ancient Mesopotamian Gardens and the Identification of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Resolved". Garden History. 21 (1): 1–13. doi:10.2307/1587050. JSTOR 1587050.

- Day, Jo (2010). "Plants, Prayers, and Power: the story of the first Mediterranean gardens". In O’Brien, Dan (ed.). Gardening Philosophy for Everyone. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 65–78. ISBN 978-1-4443-3021-2.

- Desmond, Ray (2007). The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. London: Kew Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84246-168-6.

- Drayton, Richard (2000). Nature's Government: Science, Imperial Britain, and the 'Improvement' of the World. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05976-2.

- Guerra, Francisco (1966). "Aztec Medicine". Medical History. 10 (4): 315–338. doi:10.1017/s0025727300011455. PMC 1033639. PMID 5331692.

- Heywood, Vernon H. (1987). "The changing rôle of the botanic gardens". In Bramwell, David; et al. (eds.). Botanic Gardens and the World Conservation Strategy. London: Academic Press. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-12-125462-9.

- Hill, Arthur W. (1915). "The History and Functions of Botanic Gardens" (PDF). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 2 (1/2): 185–240. doi:10.2307/2990033. hdl:2027/hvd.32044102800596. JSTOR 2990033.

- Holmes, Edward M. (1906). "Horticulture in Relation to Medicine". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 31: 42–61.

- Huxley, Anthony (ed. in chief) (1992). The New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-56159-001-8.

- Hyams, Edward & MacQuitty, William (1969). Great Botanical Gardens of the World. London: Bloomsbury Books. ISBN 978-0-906223-73-4.

- Klemun, Marianne, The Botanical Garden, EGO - European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2019, retrieved: March 8, 2021 (pdf).

- Minter, Sue (2000). The Apothecaries' Garden. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-2449-8.

- Mueller, Ferdinand von (1871). The objects of a botanic garden in relation to industries : a lecture delivered at the Industrial and Technological Museum. Melbourne: Mason, Firth & McCutcheon.

- Ogilvie, Brian W. (2006). The Science of Describing: Natural History in Renaissance Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-62087-9.

- Simmons, J.B.; Beyer, R.I.; Brandham, P.E.; Lucas, G. Ll.; Parry, V.T.H., eds. (1976). Conservation of Threatened Plants. London: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-32801-5.

- Spencer, Roger; Cross, Rob (2017). "The origins of botanic gardens and their relation to plant science with special reference to horticultural botany and cultivated plant taxonomy". Muelleria. 35: 43–93. doi:10.5962/p.291985. S2CID 251005623.

- Taylor, Patrick (2006). The Oxford Companion to the Garden. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866255-6.

- Thanos, C.A. (2005). "The Geography of Theophrastus' Life and of his Botanical Writings (Περι Φυτων)". In Karamanos, A.J.; Thanos, C.A. (eds.). Biodiversity and Natural Heritage in the Aegean, Proceedings of the Conference 'Theophrastus 2000' (Eressos – Sigri, Lesbos, 6–8 July 2000). Athens: Fragoudis. pp. 23–45. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Toby Evans, Susan (2010). "The Garden of the Aztec Philosopher-King". In O'Brien, Dan (ed.). Gardening Philosophy for Everyone. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 207–219. ISBN 978-1-4443-3021-2.

- Williams, Roger L. (2011). "On the establishment of the principal gardens of botany: A bibliographical essay by Jean-Phillipe-Francois Deleuze". Huntia. 14 (2): 147–176.

- Wyse Jackson, Peter S. & Sutherland, Lucy A. (2000). International Agenda for Botanic Gardens in Conservation (PDF). Richmond, UK: Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- Wyse Jackson, Peter S. (1999). "Experimentation on a Large Scale – An Analysis of the Holdings and Resources of Botanic Gardens". BGCNews. 3 (3): 53–72. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009.

- Young, Michael (1987). Collins Guide to the Botanical Gardens of Britain. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-218213-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Conan, Michel, ed. (2005). Baroque garden cultures: emulation, sublimation, subversion. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884023043. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- Johnson, Dale E (1985). "Literature on the history of botany and botanic gardens 1730–1840: A bibliography". Huntia. 6 (1): 1–121. PMID 11620777.

- Monem, Nadine K., ed. (2007). Botanic Gardens: A Living History. London: Black Dog. ISBN 978-1-904772-72-9.

- Rakow, Donald; Lee, Sharon, eds. (2013). Public garden management. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. ISBN 9780470904596. Retrieved 21 February 2015.